This is my updated effort to craft an overview of environmental justice – what it is, what it means in Evanston, and potential paths for the future.

What do we mean by environmental justice?

Environmental justice recognizes that our history of racial discrimination leads to current and on-going environmental, health and quality-of-life harms. We must repair the physical environment and systems that led to these harms while simultaneously building more equitable policies, practices and outcomes in the future.

Evanston’s Environmental Justice Resolution, adopted by the City Council in 2020, lays this out clearly.

“Environmental Justice (EJ) is when every resident experiences the same degree of access to environmental assets, protection from environmental hazards and health risks, and an opportunity to play an effective role in making decisions that affect the quality of life in this community.”

But the definition is only meaningful if we also recognize and label the historical injustices which create the current state. The EJ Resolution begins with: “WHEREAS, generations of Black Evanstonians, along with Latinx and other communities of color in the City of Evanston, have disproportionately experienced environmental injustice in the past, and need an environmental justice policy implemented in the City to address such issues that currently exist and may arise in the future.”

EJ, then, requires:

- Equity in access to environmental assets.

- Equity in protection from environmental hazards and health risks.

- Equity in opportunity to participate in making decisions that affect quality of life.

- Addressing EJ issues that currently exist as a result of historical injustices.

- Addressing EJ issues that may arise in the future.

Maps tell the story

The 2022 Evanston Process for Local Assessment of Needs (EPLAN) helps set the baseline for understanding the legacy impact of discriminatory policies and practices on community well-being.

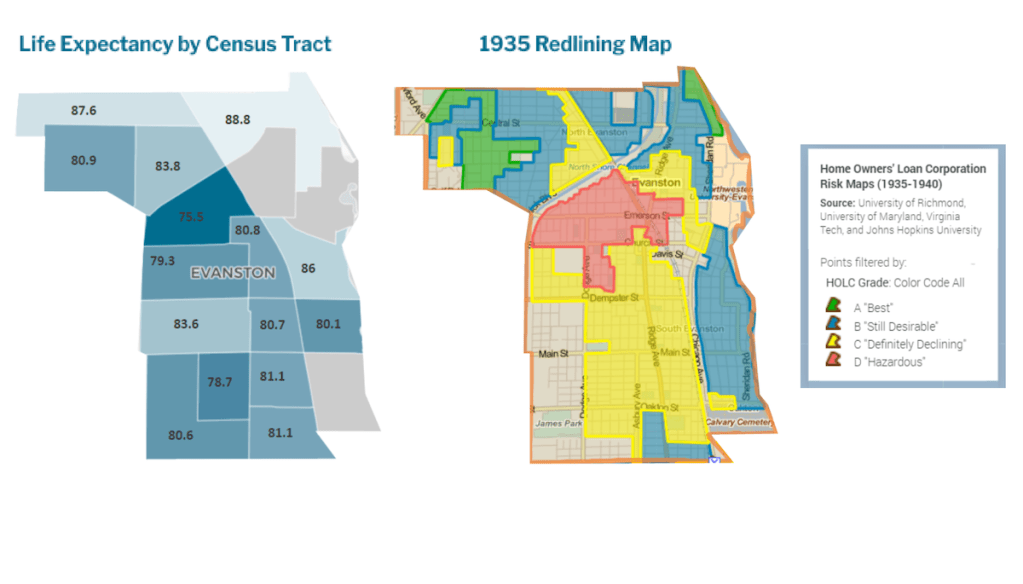

The map below (Source: Evanston EPLAN) compares the 1935 housing redlining map with current life expectancy across segments of the city. The darkest blue area on the life expectancy map – which corresponds closely with the redlined section of the city – highlights a life expectancy of 75.5 years. Evanston as a whole has an average life expectancy of 82 years. The whitest and wealthiest sections of the city have a life expectancy of 88.5 years, 13 years more than the historically redlined section.

“Comparing these two maps demonstrates the extent to which our history and ongoing practices of racism and disinvestment shape our health. Throughout the findings outlined in this report, we can observe these geographic patterns of concentrated health and privilege, as well as concentrated disinvestment and poor health.” – Evanston EPLAN

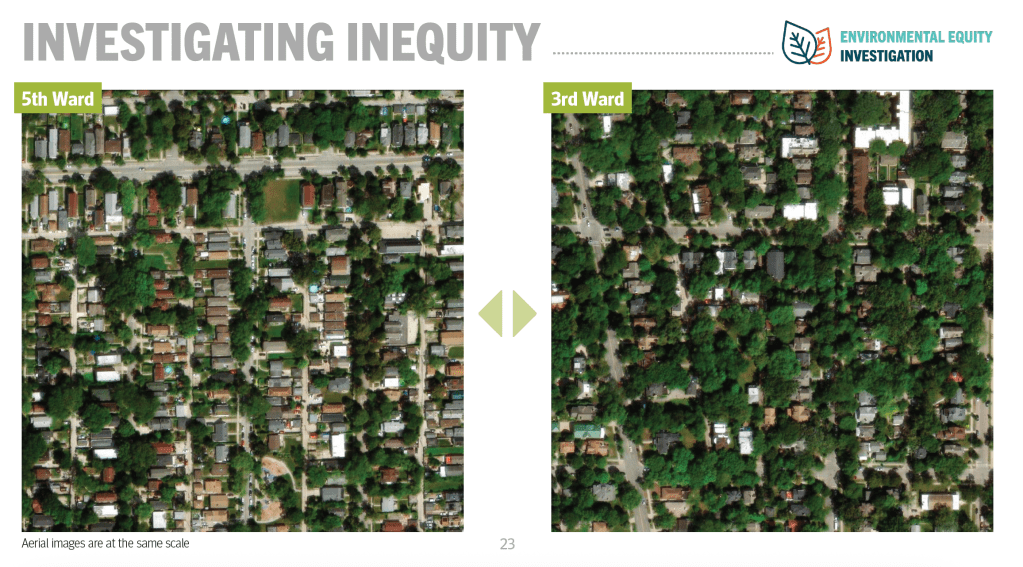

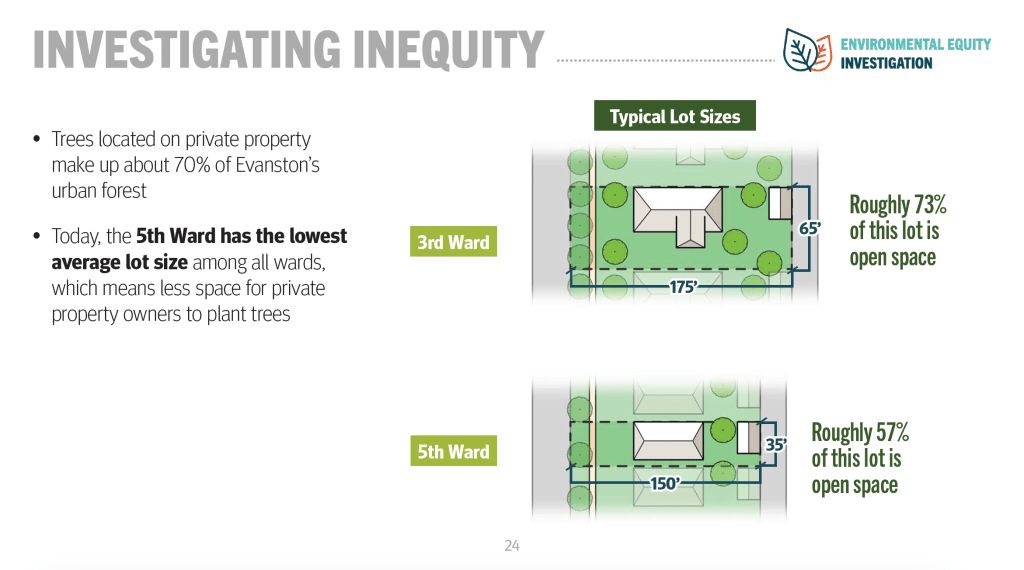

Mapping exercises conducted as part of the Evanston Environmental Equity Investigation show patterns corresponding to the EPLAN map. For example: Aerial photos and maps of the city tree canopy (tree coverage of neighborhoods) clearly depicts a more sparse canopy in the sections of the city deemed “undesirable” or “definitely declining” in the 1935 redlining map. Zoning policies contributed to this outcome by enforcing larger lot sizes in wealthier neighborhoods, resulting in more open space for tree growth.

(Source: Evanston Environmental Equity Investigation)

Cumulative impact in urban settings

Environmental equity in an urban setting involves taking a cumulative impact view. Many factors contribute to community health, well-being and (ultimately) sustainable, climate-change resilient environments. Harm is created when the benefits of these factors are absent, ignored and/or receive unequal investment.

This is outlined in an article by Evanston Environmental Justice co-leaders Jerri Garl and Janet Alexander Davis. They note a variety of conditions uncovered during research conducted as part of Evanston’s Environmental Equity Investigation. The list is not exhaustive, but representative of the cumulative impact of what might appear to be unconnected elements.

- “Few or no shade trees, even in some parks, and existing trees that need management. Lack of shade in these areas is correlated to higher temperatures, higher energy costs and potential reduction of air quality and stormwater management. Greater tree coverage correlates to higher property values.

- The lack of and poor condition of sidewalks that lead to hazards and reduced access to transit, schools/jobs and other destinations.

- Limited transit access, service, and bus shelters, especially in low-income areas where car ownership is low.

- Poorly graded alleys that shed water onto properties and hold water that attracts pests.

- Truck routes and high volume traffic corridors that result in air pollution, noise and damaging vibrations.

- Inadequate street lighting that can lead to personal safety and security issues.

- Lack of affordable housing and concentrated areas of multi-unit housing.

- Greater potential for lead exposure in older homes, where lead abatement is cost prohibitive.

- Less ability to bear the costs of replacing lead drinking water service lines.

- Blighted properties that reduce neighborhood property values.

- Nearby industrial land uses, e.g., the Waste Transfer Station, Tapecoat Corporation and other industries.

- Issues with trash collection that attract rodents, especially at multi-unit buildings.”

(Source: Evanston Roundtable)

History: The waste transfer station

Evanston’s waste transfer station stands as an example, in common with many situations that energized EJ movements across the country, where a lower-income, minority neighborhood is subjected to harms that would not be tolerated in wealthier sections of the city.

A waste transfer station is an operation where garbage is consolidated before transfer to a landfill. The lone waste transfer station in Evanston sits in a historically Black neighborhood, subjecting residents to noise, pollution, odors and pests.

A detailed history of how this operation came to be and how the community responded over time is documented in this Evanston Roundtable article by Mary Gavin. The operation continues today, more than 40 years after it started, in spite of community efforts.

What emerges in Gavin’s history a story of how a network of community organizations worked with local residents to demand actions by the city. Part of this effort led to researching and documenting the environmental conditions of the neighborhood. Air pollutants and noise, for example, were at levels that raised legitimate concern. Jerri Garl and the Environmental Justice Evanston team shared insights in Final Air Quality Study Only a Beginning (Roundtable article).

But the story also points to a Gordian Knot of issues and interests that ultimately lead to continuing inaction to resolve the harms produced by the transfer station:

- Evanston benefits by collecting revenue – tonnage fees – from the transfer station operator.

- Attempts to mitigate the harms led to years of litigation and delays.

- Operators of the transfer station have changed hands (now operated by $6B waste management corporation).

- A lack of effective, coherent safeguards and coordination exists among responsible local, state and federal agencies.

- A few dedicated community activists continue to press for accountability, but the general citizenry of Evanston exerts much more attention and energy to issues affecting single-family zoning code, or the scale of proposed high-rise developments in downtown.

The future

A key question is: How might we repair the physical environment and systems that led to existing harms while simultaneously building more equitable policies, practices and outcomes in the future?

Three potential paths offer opportunities. Others may emerge but current community efforts are aligning around these three.

The bureaucratic path. This path focuses on city policy, staff and operations. Embedding EJ in city policy and practice is an immensely complex challenge to which there are many possible productive solutions, and each deserves attention. But some options provide greater leverage. For example: A comprehensive EJ city ordinance would play a pivotal role here, establishing EJ more deeply into the laws which govern the city.. Policy and practice ideas emerging out of the Evanston Environmental Equity Investigation (EEI) also set up the potential for clear, broad accountability over the long term. For example: One idea is to declare the lower-income, historically Black/Brown city neighborhoods as on-going, designated EJ focus areas. These EJ focus areas would be “green zones” that have priority for new green investment.

The community engagement path. This path has been cleared for the past decade through the leadership of Jerri Garl and Janet Alexander Davis and Environmental Justice Evanston. In addition to spearheading advocacy to address the waste transfer station, the duo’s work led to development and passage of the city’s environmental justice resolution and to the city committing budget and resources to launch the Environmental Equity Investigation (EEI). The two play formal roles in the EEI process and continue to shape its work. Jerri and Janet also have partnered with other Evanston civic organizations who began their own environmental justice efforts. This growing network led to the newly-formed Evanston Environmental Justice Coalition – a structure to bring together diverse groups and their resources to address local environmental and climate justice challenges.

Community engagement is also an immensely complex, and unending, challenge. You can always get better at lifting the voices of the city’s most vulnerable populations and designing solutions with them, rather than for them. But the Evanston Environmental Justice Coalition is positioned to play a potentially important role in building the infrastructure to support the community engagement path.

The political path. This path is as yet undeveloped. It came to light through the wisdom and experience of Janet Alexander Davis. She calls out the current state as being dominated by political-consultant-led language and thinking which influences how our political leaders operate and engage. Instead, Janet argues, we must uplift the experience and language of low-income, working people, across generations, and center their needs as core to the political agenda. Using their language. For EJ advocates, this means being more explicit and active in discovering opportunities to add a political element to its advocacy work.

These three paths clearly criss-cross and merge together at points. That may be the most important mindset looking toward the future: Seeing the EJ challenge through multiple lenses and finding the opportunities for collective and cumulative impact.

Related posts

Three ways of framing the environmental justice problem, by the folks who know.

‘Why is this happening to us? We know why it’s happening.’

Notes on Evanston environmental equity

Notepad: Thinking through how to teach environmental equity

The photographs which accompany these posts are taken by me, and show different settings and views of Evanston (where I live). It is a visual reminder that this is the most important setting for belonging and contributing to community: our neighborhoods, our cities.

2 thoughts on “Update: Evanston environmental justice”

Comments are closed.