I recently attended two half-day working sessions of the Evanston Environmental Justice (EJ) Coalition. The sessions were designed to inform a strategy for this new organization as it moves into 2026.

I was geeked for a number of reasons. This was front-row observation of community coalition building with folks who (unlike me) have deep experience in that space. It was also an opportunity for me to find a more active role where I might contribute (and that opportunity emerged – I am helping lead a communications and community engagement team). And finally, it gave me a chance to meet Evanston folks who bring incredible personal expertise across a number of fields.

It’s that last bit – personal expertise – that I want to highlight in this post.

Each half-day working session included roughly a dozen people representing diverse community organizations, directly or indirectly connected with one or more aspects of environmental justice. One of the things that struck me, starting in the first session, was the level of humility displayed, even as folks offered thoughts based on their deep expertise.

What I recall from research on the differences between novices and experts is that people with deep expertise recognize how they frame a problem in front of them, and they also know what they don’t know. I saw both of these at play during the working sessions. No one naively or confidently offered one “best” path to success. They all saw it from different angles. And each angle humbled them in a way that comes from experience and expertise dealing with complex human problems.

And EJ is a complex human problem. A definition that has meaning for the EJ Coalition comes from Evanston’s Environmental Justice Resolution: “Environmental Justice (EJ) is when every resident experiences the same degree of access to environmental assets, protection from environmental hazards and health risks, and an opportunity to play an effective role in making decisions that affect the quality of life in this community.”

How do we think about that vision as a problem to be solved? Three framings (that I noted) emerged during the sessions. I want to capture these because of the importance of framing problems. How you frame a problem is how you solve it; framing guides our thinking. What helps, in my experience, is having the ability to simultaneously work through multiple frames.

Here are my summaries of the three that emerged from the meetings.

A bureaucratic problem

This framing centers city policy, staff and operations. A critical tool here is city ordinances – the laws by which cities operate and hold themselves accountable. The first challenge is in pulling togeher community consensus, legal expertise, and political power to put ideas into language which will guide city activities to achieve some desired outcome. The second challenge is in ensuring city staff – burdened by a complex system of ordinances and policies – follow through on the intended behaviors, direction and outcomes of approved governing ordinances. EJ Coalition members include folks with years of experience in both of these challenges.

In the EJ case, Evanston passed a formal resolution in 2020 that commits the city to several EJ actions, including passage of an EJ ordinance to formalize the intended direction outlined in the resolution. The ordinance is currently nowhere among the many items being considered by the city. Other actions outlined in the resolution – the creation of a map tool, for example, using data to showcase differences in health, environment and livability outcome across neighborhoods – have also not moved forward. It appears most of the good actions spelled out in the EJ resolution simply ground to a halt under the daily workload of operating a functioning city.

However, those folks who know how the city ultimately gets stuff done noted that it’s important to leverage work – like the EJ Resolution – that is already on the books. And across the Coalition are folks who know how to continue doing this kind of work.

A community engagement problem

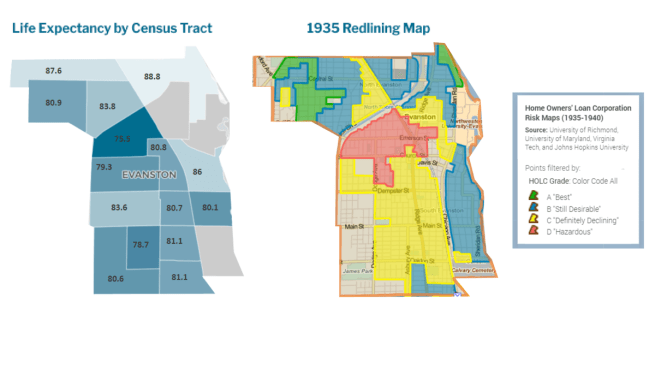

In this framing, the challenge is engaging community members whose voices are excluded – unintentionally or intentionally – and who disproportionately bear the cumulative negative impacts of that exclusion. Maps tell the story here.

The map below (Source: Evanston EPLAN) compares the 1935 redlining map with current life expectancy across segments of the city. The darkest blue area on the life expectancy map – which corresponds closely with the redlined section of the city – highlights a life expectancy of 75.5 years. Evanston as a whole has an average life expectancy of 82 years. The whitest and wealthiest sections of the city have a life expectancy of 88.5 years – 13 years more than the historically redlined section.

Maps generated as part of the Evanston Environmental Equity Investigation show a very similar story when you look at environmental assets (i.e., tree canopy, open spaces) or burdens (location of a waste transfer station, truck routes, etc.).

Engaging community members who live in these affected areas is a challenge that has both logistical elements and power elements.

It’s very difficult, logistically, to reach and then engage low-income working folks. We heard stories during the strategy sessions of folks who have the desire and inclination to be more involved in civic decisions, but their lives left little time and emotional space to engage. Add to that one aspect of the power problem – are we being asked to engage to simply meet some demographic metric, but really the decisions are already made? – and you begin to see the vicious cycle of disengagement and lack of trust making the logistical problem even more challenging.

The power element goes even deeper.

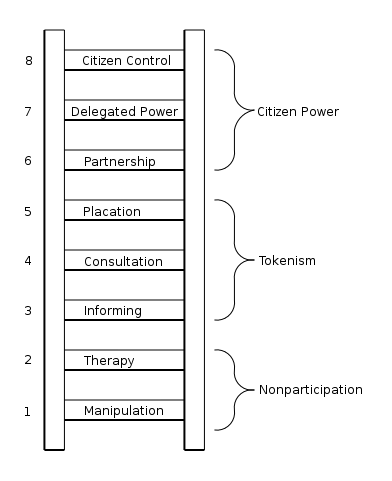

Work that began in the 60’s resulted in a model which is still used today – the Arnstein Ladder. The model became a discussion point during the EJ Coalition strategy sessions.

At the lower rungs of the ladder, citizens are passive recipients of programs and services with no real participatory power. The middle rungs are activities that disguise the still-existing power relationships (tokenism, or extracting information or ideas that benefit the designers more than the community). At the top rungs, citizens have real power, either delegated to them (participatory budgeting may be an example) or where they exercise full control.

Arnstein Ladder

By DuLithgow - As part of publishing an article online Previously published: http://lithgow-schmidt.dk/sherry-arnstein/ladder-of-citizen-participation.html, CC BY 3.0,

The deeper challenge is legitimately moving up the ladder. How might communities move beyond tokenism – which I see in Evanston – toward partnership (co-creation) and citizen control? Where more power is held by those who have been historically disadvantaged? Those questions also lead into the final framing.

A political/social power problem

Look at all of the hand-wringing after the election of Zoran Mamdani as Mayor of NYC. He clearly represents a threat to the white male, moneyed, dominated power structure. It’s fear we are seeing. Even those folks who seem to appreciate the direction of some of his policies – free child care, free busses – give up in advance with a “well, that will never happen…” mindset posing as “reality.”

In a way, all of those folks are correct. Reality is that folks aligned with the dominant system will use all of their power and resources to fight back and maintain control. And this point was made explicitly during the EJ Coalition strategy session discussions. It came about in two ways.

First was a reminder from a participant who works for a not-for-profit dedicated to addressing racial and social justice, with a long professional and educational career in that field: We need to remember that we are engaged in a continuous struggle between two systems. One which exploits and extracts to gain power, and one which builds equity, justice and community. In doing this he gently reminded all of us that the problem we face is situated in a long, continuous historical struggle.

Second was from a long-time Evanston community civil rights leader. The commentary came as a general dissatisfaction with all current political parties and leaders – including local leaders. Evanston sees itself as a very progressive community and voters lean heavily Democrat (close to 90% in the last few national elections). But even locally, noted this leader, no one truly speaks for and fights effectively for low-income, working folks. All the work is driven by the language and ideas of political consultants. She noted all of this while calling out a need for the group to always have one eye on the political landscape, and perhaps rethink how it contributes to that landscape.

Both these points, to me, force the strategy group to step back and acknowledge that political landscape and the power dynamics at play. It’s not an entirely comfortable place to be when you need to focus on the on-the-ground details of crafting policy or designing ways to better engage community members.

What it means

The sense I got from the strategy group is that its collective expertise and deep real-world experience will lead to discovering new opportunities to move the needle. This is not naiveté. It is that collective expertise and experience speaking.

The long road and hard work to develop and pass the EJ Resolution created a foothold that is still relevant today. It helped solidify relationships that still exist today. All of those are assets. The community engagement work that many of the coalition members do offers new points of opportunity to reach and engage folks through existing relationships, and to expand the range of those relationships. That is also an asset. And those relationships all build political power. Another asset to be developed.

We have assets. That idea was also explicitly used during the strategy session. How might we use the assets we have, in new ways, to help create the type of community that walks-the-walk when it comes to environmental justice?

The photographs which accompany these posts are taken by me, and show different settings and views of Evanston (where I live). It is a visual reminder that this is the most important setting for belonging and contributing to community: our neighborhoods, our cities.

2 thoughts on “Three ways of framing the environmental justice problem, by the folks who know.”

Comments are closed.