This post contains a few notes and resources about the status of environmental equity in Evanston.

Understanding the map

The 2022 Evanston Process for Local Assessment of Needs (EPLAN) helps set the baseline for understanding the legacy impact of discriminatory housing policies and practices on community well-being.

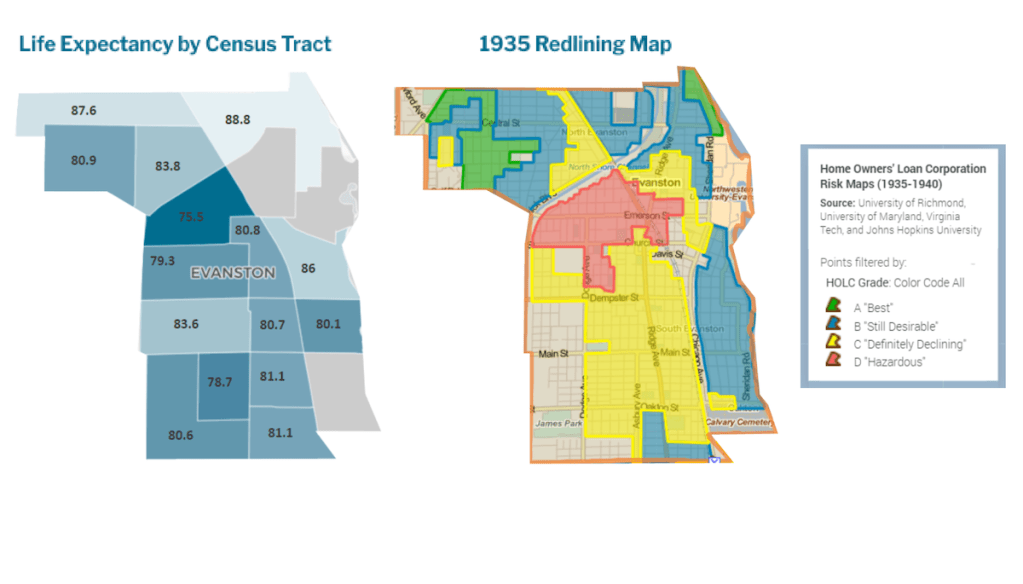

The map below (Source: Evanston EPLAN) compares the 1935 redlining map with current life expectancy across segments of the city. The darkest blue area on the life expectancy map – which corresponds closely with the redlined section of the city – highlights a life expectancy of 75.5 years. Evanston as a whole has an average life expectancy of 82 years. The whitest and wealthiest sections of the city have a life expectancy of 88.5 years – 13 years more than the historically redlined section.

“Comparing these two maps demonstrates the extent to which our history and ongoing practices of racism and disinvestment shape our health. Throughout the findings outlined in this report, we can observe these geographic patterns of concentrated health and privilege, as well as concentrated disinvestment and poor health.” – Evanston EPLAN

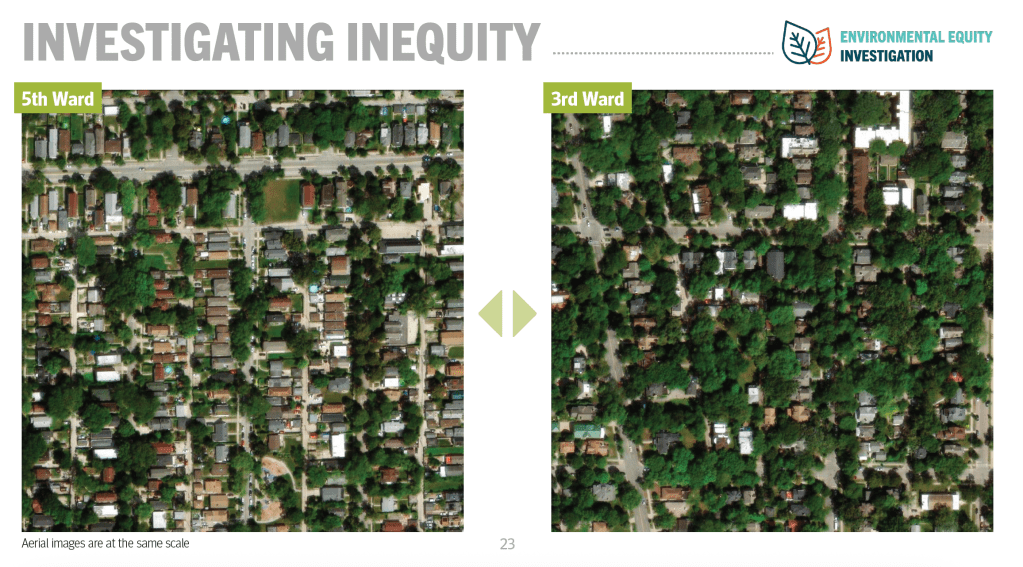

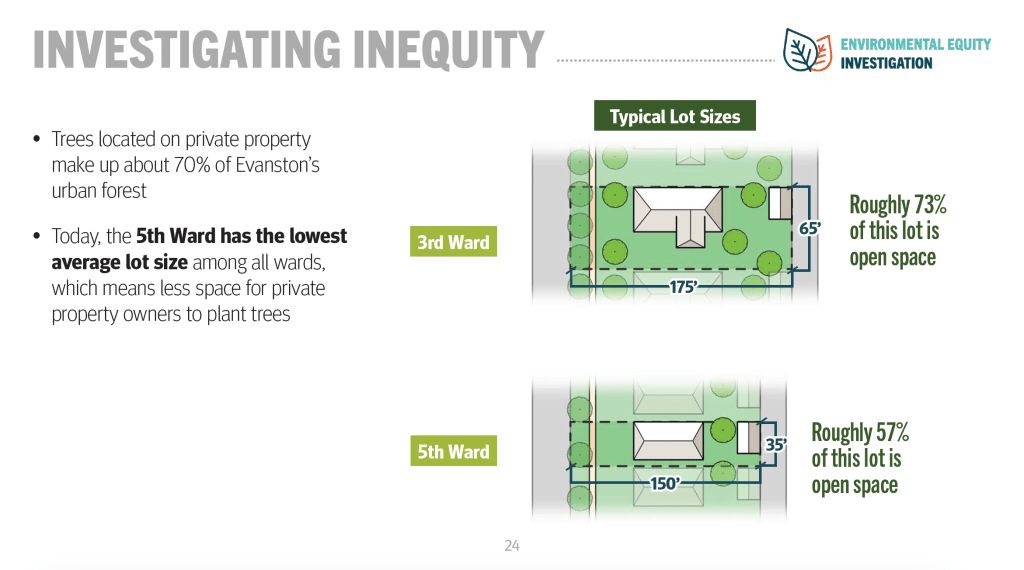

Mapping exercises conducted as part of the Evanston Environmental Equity Investigation show patterns corresponding to the EPLAN map. For example: Aerial photos and maps of the city tree canopy (tree coverage of neighborhoods) clearly depicts the sparse canopy in the sections of the city deemed “undesirable” or “definitely declining” in the 1935 redlining map.

(Source: Evanston Environmental Equity Investigation)

The urban systems view

Environmental equity in an urban setting involves taking a systems view. What factors contribute to community health, well-being and (ultimately) sustainable, climate-change resilient environments?

This is outlined in an article by Evanston Environmental Justice co-leaders Jerri Garl and Janet Alexander Davis. They note some preliminary themes uncovered during early discovery conducted as part of Evanston’s Environmental Equity Investigation.

- “Few or no shade trees, even in some parks, and existing trees that need management. Lack of shade in these areas is correlated to higher temperatures, higher energy costs and potential reduction of air quality and stormwater management. Greater tree coverage correlates to higher property values.

- The lack of and poor condition of sidewalks that lead to hazards and reduced access to transit, schools/jobs and other destinations.

- Limited transit access, service, and bus shelters, especially in low-income areas where car ownership is low.

- Poorly graded alleys that shed water onto properties and hold water that attracts pests.

- Truck routes and high volume traffic corridors that result in air pollution, noise and damaging vibrations.

- Inadequate street lighting that can lead to personal safety and security issues.

- Lack of affordable housing and concentrated areas of multi-unit housing.

- Greater potential for lead exposure in older homes, where lead abatement is cost prohibitive.

- Less ability to bear the costs of replacing lead drinking water service lines.

- Blighted properties that reduce neighborhood property values.

- Nearby industrial land uses, e.g., the Waste Transfer Station, Tapecoat Corporation and other industries.

- Issues with trash collection that attract rodents, especially at multi-unit buildings.”

(Source: Evanston Roundtable)

History: The waste transfer station

A waste transfer station is an operation where garbage collected from the city is consolidated before transfer to a landfill. Evanston’s sits in a historically black neighborhood, subjecting residents to noise, pollution, odors and pests.

A detailed history of how this 40-year operation came to be, and how the community responded over time, is documented in this Evanston Roundtable article by publisher Mary Gavin. It includes details of the early work of Environmental Justice Evanston (EJE). What emerges, in part, is a story of how EJE worked with local residents to ensure actions were taken by the city to responsibly research and document the environmental conditions of the neighborhood. Air quality, for example, was found to be impacted. Garl and the EJE team shared insights in Final Air Quality Study Only a Beginning (Roundtable article).

The history also points to this network of community organizations and environmental activists as critical in holding the city accountable for using funds – generated by fees paid to the city by waste management companies – to address the situation.

3 thoughts on “Notes on Evanston environmental equity”

Comments are closed.